For DBG, who asked me multiple times this year when my newsletter was coming back. I’m sorry I didn’t do it sooner. I would have loved to talk about this with you.

I bought Molly before the discourse began. I’d been looking forward to the book all year. At its worst, I consider my appetite for writers writing about the death of other writers macabre and voyeuristic. In a more forgiving reading, I think it’s one of the purest expressions of the human as a vessel for art and the love and terror that inevitably follows.

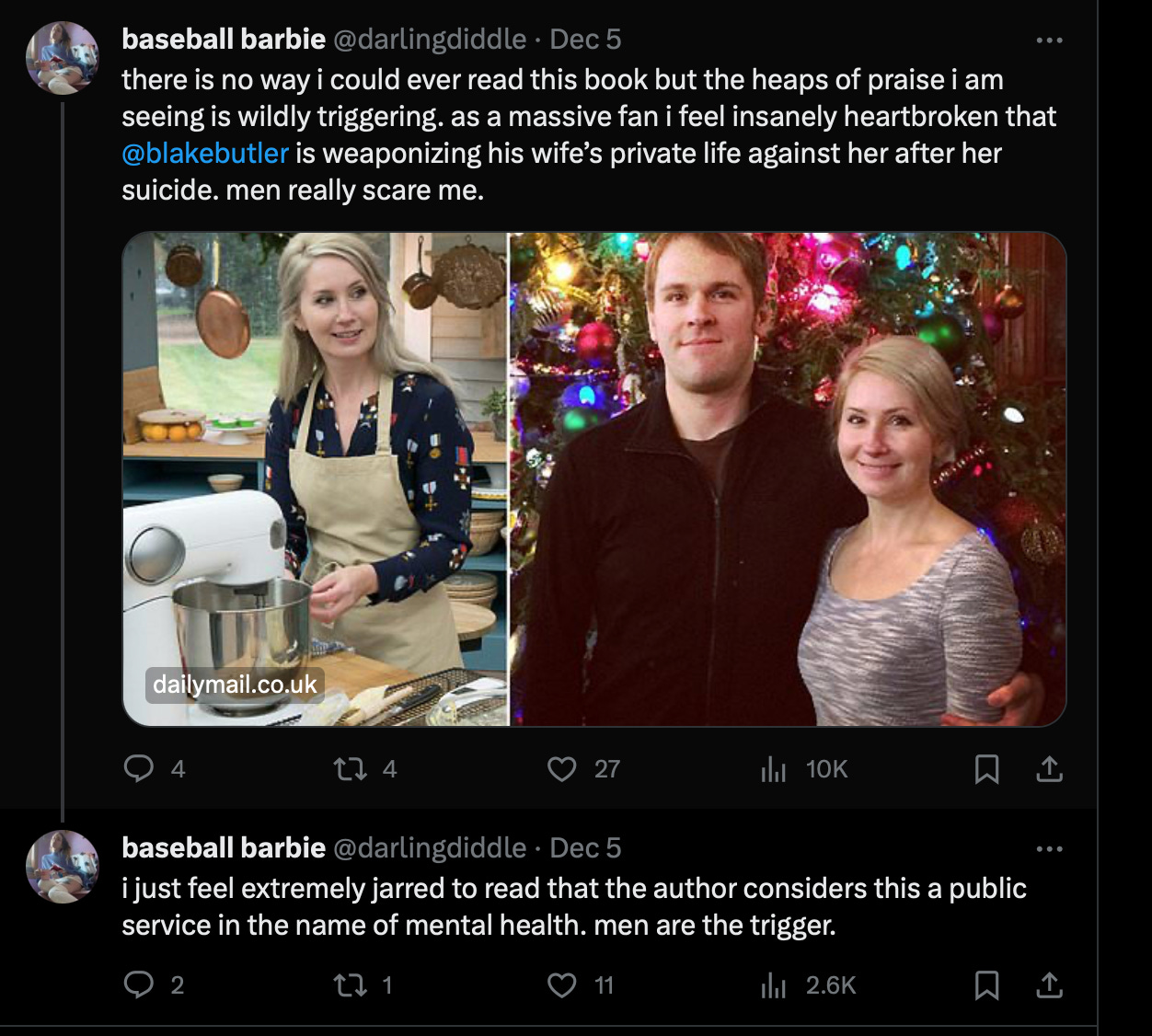

All this was on my mind. Then came the discourse. ICYMI,

You can’t just say things are other things! The internet these days is like a game of putting your hand into a pot of vaguely thematic buzzwords and picking out an accusation that matches your mental crusade. Evidence of pain is not the same as posting pornography as revenge!

This tweet thread spawned a torrent of insipid criticisms from the smallest minds of the literary internet. Someone said that Butler should have kept his processing in therapy. Everyone cried misogyny, and, seemingly, no one read the entire book.

One writer even made a ‘collage’ of ‘bad writing’ from an excerpt of the book online. I went to her personal website and read her poetry — I will refrain from reposting here, but her feeling entitled to make a ‘collage of bad writing’ was quite ironic.

Beyond the smooth-brained claims laid out in these tweets, I sensed an underlying discomfort: people get upset when art portrays the fact that some people don’t get better. Is it a strange cousin of poptimism? This idea that if people stop portraying the fact of incurable depression, it will cease to exist?

Criticizing a book actually won’t change the inalienable truth that some people, for whatever reason, are going to die instead of heal. I saw similar reactions to A Little Life; that portraying Jude as someone who never got better (spoiler alert?) was somehow going to discourage people who do manage to thrive after trauma. But both exist. “It gets better” for some people, but not for others. Literature shouldn’t be imprisoned by the logic of Dan Savage’s nonprofit.

Some of the claims made by the tweeters become entirely irrelevant when you actually read the book: Butler does not actually publish the sexts. He says they exist, but he does not quote them.

Well then, he still quoted from her diary! But things start to fall apart here. Dead people’s private words have been published for hundreds of years. Would you like to write a treatise about when it is allowed and when it is not? Okay, message me when it’s done!

Who has torn Molly, the person, apart in the aftermath? All I’ve seen is people exhibiting sorrow, empathy, and grace. Why are women allowed to process their grief through creative work, but not men? Calling a book published by an independent press a ‘cash grab’ is laughable to anyone who has actually spent time in the publishing community. To the tweeter who asked, can’t some things stay in therapy? Well, can’t some fights stay private? What was the point of furthering this man’s pain by forcing him into a discourse full of baseless accusations?

When I finished the book, I found that the author had thanked one of the hateful tweeters in the acknowledgments. I felt sick. If you know someone well enough to be thanked in the acknowledgements of their book, do you not owe them a more private conversation than a subtweet that becomes an ugly discourse?

The ultimate question of the book really isn’t that complicated and doesn’t need to come down to these petty, and in many cases invented, grievances. The only question is, did he write the truth? There has been zero indication to the contrary.

Readers (or not readers, as the case may be,) may be uncomfortable with what he unearthed about his late wife’s behavior, but to blame Butler for unearthing it is an old trick, one that any true critical thinker should have moved past long ago.

It happened. Asking someone to sit in silence with their experience is counter to the ongoing project of personal art, and cherry picking who gets to tell their story and who doesn’t will only backfire.

Of a nearly 300 page book, the revealing of infidelity that sparked the Twitter discourse takes up maybe five pages. To call the work vindictive is operating purely on assumptions of what the book might be, not at all an examination of what it actually is.

From an LA Times review of the book:

“Butler’s experience recalls that of Ted Hughes in the wake of Sylvia Plath’s death. But unlike Hughes, who destroyed Plath’s last journals and set down the iron curtain on her last days, Butler rather bravely and obsessively goes through Molly’s final journals, poems, emails and social posts, sharing them not only with the lunacy of the bereaved lover but, thankfully, the brilliance and drive of a writer.”

It begs the question: Are the detractors really holding up someone like Ted Hughes as the paragon of appropriateness in the wake of a suicide? Is his behavior what we want from those who are left living? Similar questions were asked in the wake of the publication of Truth and Beauty, Ann Patchett’s memoir about her late friend, the poet Lucy Grealy.

The elementary reading in both cases being: the author said some unattractive things about the dead. But how immature must we be as readers to read an unattractive thing about a person and assume that is tantamount to a negation of their personhood?

In both books, the author loved the deceased. To love someone truly is not to deify them, it is to see them from every angle, even the worst possible, and love them just the same. To read these books as a form of revenge is to have no understanding of what it means to love, to share a life, to know someone deeply. Viewing our lost loved ones as perfect monoliths is more shameful to their memory than being honest about their flaws. What is the point of writing about the past if not to unearth its ugly underbelly and attempt, in some way, to come to terms with it?

It’s small minded and childish to assume that because someone revealed some unsavory behavior of a dead person, that person’s memory is besmirched forever. We don’t need to live in a world where a whiff of ickiness puts someone in the doghouse of the afterlife. Butler, in his publishing, was trusting readers to give Molly the grace they’d extend to a loved one, it’s a shame that the book’s publication was marred by so many people quickly failing that test.

No one has claimed that Molly was a bad person because of what she did. Butler certainly didn’t. Only a plebian would read the book (or not read it, of course, as the case has been,) and believe that Blake didn’t honor Molly. Blind honor isn’t honor at all.

Luckily, many serious literary people have come to Butler’s defense. I hope that they’re giving him the emotional care in private that is so needed in a situation where one is being attacked by strangers online.

The professional critics who have actually read the book have reacted with much more compassion than people yelling about its imagined premise online.

From The Telegraph "the triumph of his book lies in its compassion. Instead of shaming Brodak, he shows respect to her trickle-down trauma. He diagnoses her – I suspect accurately – with borderline personality disorder. He tells us every awful truth about a toxic relationship. And he does it with real, unending love."

From Publishers Weekly: “The tone is never vengeful or petty—Butler gracefully and intelligently sifts through the life he built with his late wife, relating their difficult tale in beautiful prose that convincingly conjures their mutual love.”

Pardon me for siding with the professional critics who read the book with fairness in mind over tweeters who didn’t read it at all.

Butler shows through his writing that he takes Molly as much more than her transgressions, the reader owes it to both of them to do the same. Butler suffered emotional abuse from his partner, but he does not belabor the point. Mourning the dead as an angelic monolith is as much a flattening as vilifying them. Butler does neither.

It’s a book that is hyper-aware of its subject: “Every sentence I write here, I imagine Molly rolling her eyes.” In these moments, the accusations of Butler demeaning his subject ring especially false. Molly is a conversation with Molly herself, and serious conversations are not meant to be elegiac platitudes.

He details not only his own transgressions, but the hurtful ways Molly described him to others. The last man Molly sleeps with describes his time with her as ‘sex work’ because she would send him money when he begged for help. Everyone’s worst sides are explored, no one is off the hook. With all the information set free, it no longer truly belongs to either Butler or Brodak: it is no longer an individual burden.

Butler writes, “In the end, I don't know what she owes anybody.” I see here a fundamental thread to the book: it is an attempt to understand rather than an understanding, with echoes of Steinbeck working towards the perfectibility of man rather than believing it exists.

I came to see the book as more than a restructuring of the past or a therapeutic attempt to understand what happened. Rather, for a person who lost their own past, it was the rebuilding of a narrative fundamental to the self. No one should be begrudged that opportunity to live again, much less an artist. In the end, his forgiveness is omniscient, that of a god who has learned to sit back and let the human chips fall where they may.

i can't remember the last time I've been more excited to buy and read a book and I wasn't even aware of the discourse surrounding it. i think this is incredibly well put, thank you for sharing.